On Monday 25 April 2022, the SOS MEDITERRANEE rescue team rescued 94 people in a complex operation with the Libyan coastguard on scene. A few hours later, survivors shared a heart-breaking event with the team onboard: 15 people on the overcrowded rubber boat fell into the water during the night. Only 3 made it back, the others likely drowned. 12 people are officially missing. Claire, communications officer, explains this sad sequence of events.

First, the search. At 09:42, the Bridge receives an email from the civil hotline Alarm Phone about a boat in distress. I climb up the stairs to reach the Bridge and to speak with the Search and Rescue coordinator: “we are 10 Nautical Miles away”. I inform the journalists on board with us.

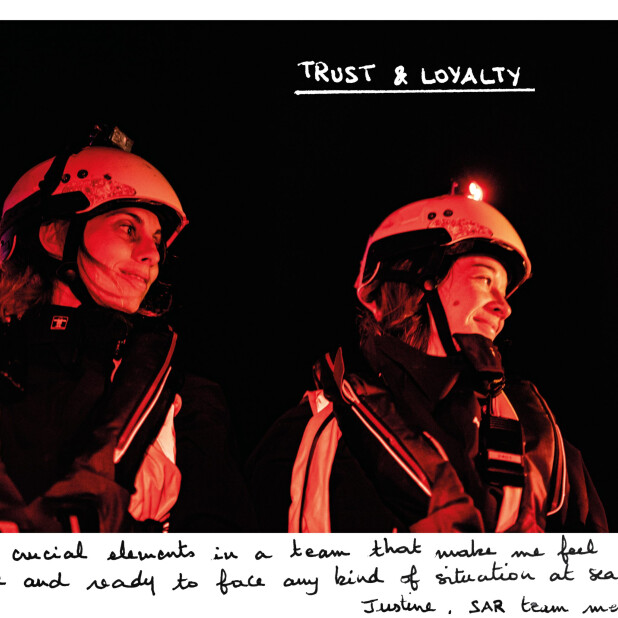

Second, “get ready for rescue”. The Search and Rescue team leader confirms the visual on the boat in distress. “All teams, all teams, get ready for rescue”. We are all prepared for this call, yet, our stomach always tightens few seconds when we hear this sentence. There are no seconds to spare: I put my rescue gears on, waterproof clothes, lifejackets, gloves, helmet, mask. I check the gears of the journalists, inform them about the latest news, take my camera, give the GO PRO to the drivers of each of our three rescue boats (Easy 1, 2 and 3).

Third, the rescue. I am on the rescue boat in charge of the first assessment of the boat in distress. It’s a white rubber boat, people are sitting on the sponsons. The dinghy is overcrowded. There is a baby and women in the middle of the boat. We start to evacuate those in distress. First, the baby. He is tiny. When I took this picture, I thought that the baby would be safe in just a few minutes, by the time he was brought aboard the Ocean Viking with the first evacuated survivors. A few seconds later, when the first rescue boat was transferring the survivors onto the mothership, the Bridge called us on the radio: “We have visitors, ETA [.i.e. Estimated Time Arrival] 11 minutes.”

“Visitors” means Libyan coastguard. They cannot be named over the radio to avoid panic among the shipwrecked people. But we know. They came yesterday during the rescue of a deflated rubber boat. They nearly made the boat capsize with the wake of their vessel and the panic they caused among the people in distress. It’s happening again. Will they be even more aggressive than yesterday? Do they want to stop the rescue? Will they be threatening us? Will the people jump in the water seeing them? They arrive at high speed, while we are evacuating people from the rubber boat. Anxiety escalates among the people. They try to jump on us to escape. They are afraid to be taken back to Libya, where they tried to escape a harrowing cycle of violence. People could fall into the water at any time. All my colleagues stay calm, and use technics of crowd control to stabilise the situation, we continue the rescue as we have been trained for. The evacuation from the boat in distress is complete. The Libyan coastguard follow our fast rescue boat to the boat landing and threateningly turn around the Ocean Viking before going back to the rubber boat to take its engine.

Fourth, the 12 missing people. Back on deck I see the post-rescue team actively caring for survivors. The midwife has the baby in her arms. I can see his face now. He is smiling. I tell myself, “it’s over, this rescue could have turned critical, but it’s over.” However, a few hours later, the post-rescue team leader comes to me, eyes down. It’s not over. “Several survivors told us that people fell overboard from the rubber boat during the night,” she says. “Only 3 were recovered. They were 106 when they left, and we rescued 94 people.”

12 people are missing. They were taken by the sea in the darkness, only a few hours before we rescued the remaining people. I go back on deck. “The horror is over”, I was telling myself not long before. The relief I felt earlier disappeared. As people settled down, I can now see what I couldn’t see before. People still in shock, withdrawn. I look at the baby, still smiling. He has no idea of what just happened. He is only one year old, I learn. He went through hell in 12 months of life. The only thing I can do is to testify, so that at least these twelve people do not disappear without a trace, so that their death is recognised.

Credit: Claire Juchat / SOS MEDITERRANEE